Zoë Randall Teacher Leadership Digital Portfolio

Findings

When I began the school year, I had a strong desire to find new ways of understanding my students and build a better classroom culture. I wanted to get to know my students. As a result of this desire, I decided to focus my action research on developing a digital storytelling project revolving around a defining moment in my 6th grade students’ lives. I wanted to help students creatively express themselves and share their stories with others. I wanted to give students an outlet to make their stories heard. I wanted to know what happened as students told stories of themselves and others through digital storytelling. I found that in the process, students discovered they all had stories to tell, and that their stories had lasting impressions not only on themselves, but also on their audience members. The following findings share the narrative of the project process as well as highlight some themes that I hope prove useful to other educators as they decide how to go about using digital storytelling in any context. I also include a few case studies of students who approached the storytelling process differently.

Building a Storytelling Community

The first few weeks were crucial in forming a strong classroom culture. It was the beginning of the year and I wanted to define a culture where students were encouraged to communicate and participate in the classroom community. I wanted them to be able to share aspects of themselves and who they are with one another. I tried many new strategies to engage students in building an empathetic community and hoped that it would encourage dialogue and a high level of comfort to share personal stories with each other. In my classroom, I wanted students to build a sense of identity through storytelling, be able to share their personal stories with each other, become empathetic to one another, and share these stories with the community.

Strategies for Building Community

In my previous years teaching in my multimedia lab, I’ve rearranged the seating several times to accommodate the different activities that students would be doing in the classroom. This year, my focus was making kids feel comfortable with the space, with me, and with each other.

Each day the students came in and sat in a circle. I didn’t dictate where they sat, but always made sure that everyone felt included in the circle and could see everyone. As a teacher, I felt like this configuration made me less like a “sage on the stage” and more of a facilitator of conversation and idea sharing. However, due to the loose seating assignments, students were extremely talkative which led to taking a longer time to settle in and quiet down. They often sat next to the people they were closest to in class, and as friendships changed, seating choices reflected those changes. After the semester ended, I invited a focus group of six students to share their thoughts and opinions on the semester. As a group, they felt that the circle provided a space to listen to directions or the agenda for the day, and that it helped people become more familiar with one another, especially in the beginning of the year. However, they agreed that starting every class period in the circle “took a long time to get people focused...and we lost a lot of our work time.”

About two weeks into the semester, I hung a large clasped envelope on my desk where students could share notes with me about anything they were feeling. I introduced it as a place to leave thoughts and feelings for students who didn’t have a chance to share during our short class period. I wanted to encourage sharing in as many different contexts as possible in the classroom, by allowing students to express their feelings with me privately when they needed. I received notes about things happening in class with others, goings-on in life, and problems that the kids were experiencing. Some notes let me know if they were feeling sad or happy.

I learned later on in my focus group interview that I didn’t promote the box very well and that if I had, more students might have used it. However, as things came up I made sure I connected with the student the next day or at the end of class to check in and see how he or she was feeling. For instance, one student left a long letter to me explaining how her heart was broken knowing that her best friend was mad at her. Something had happened in their humanities class and the two girls stopped talking to each other. This was a difficult situation because they happened to be co-producing each other’s digital stories in my classroom. I sat the two girls down in my office and had them work out an agreement, and after a few days, they resolved their conflict. In contrast, one of my focus group students remarked that, “I never used that feeling box because it’s kind of my personal life my feelings. Sometimes I don’t want to express that to...a lot of people.”His remarks helped me understand that students felt differently about sharing.

In a technology classroom, I found it vital to the community to have students share their abilities and help in the classroom as a way to promote leadership, mentorship, accountability, and responsibility in students. The tech rovers system was magical! The kids had a spot on the whiteboard where they wrote their names so that others would know that they were available as tech rovers. At the start of class I would ask students if they wanted to be tech rovers, and those who wanted to help would add their names to the list. Every day and every class had volunteers, though some students volunteered some of the time, and some did not volunteer at all. In one of my focus group interviews, I found out that students who did not volunteer usually wanted to use all their time in class to work on their own project. One of my students felt she didn’t have enough computer skills to help, which was quickly shot down by another focus student who exclaimed, “I think she was amazing with the computer.” Students who did volunteer signed up because they felt like helping or finished their work early. They did not sign up if they felt people did not need their help.

I attempted to make sure I was requesting tech rovers to sign up for help in a variety of skills so that different students were able to contribute. Some examples of these expertise areas included Photoshop, creating a digital portfolio in Google Sites, editing in I-Movie, connecting to the school server, connecting a flash drive, connecting a digital camera, and general tech troubleshooting. I usually made a point in the beginning to ask for various special requests for students who felt comfortable in these areas. Although posting a variety of skills produced some changes in who signed up, it didn't keep a record that would have allowed me to show patterns and track student behavior.

This buddy system was important to establish a sense of community and peer mentoring. I wanted to demonstrate that good projects could not be assessed without help and critique from another peer. Every student had a buddy who was responsible for offering kind, helpful, specific critique on their digital story throughout the production process. In my classroom, this buddy system was particularly conducive to the learning environment because we have a 2:1 computer ratio, and every student had to share their Mac G5 workstation with a buddy.

I also found that the buddy system helped keep students accountable to themselves and to others.Every student had a checklist of tasks that their buddy had to sign before they could go on to the next task. Before pairing students up as Co-Producers of digital stories, we did some initial computer skills building with a buddy of their choice. As part of this, I asked them to email me “Buddy Expectations” so that we could establish classroom standards for what we expected from each other. One of my focus students who didn’t always like sharing openly with the class surprisingly mentions sharing as part of his and his buddy’s expectations:

•Not to say things that are not TRUE.

•Work together.

•Be NICE to each other.

•Respect each other.

•Listen to each other.

•SHARE.

Another interesting model came from Tim and his partner:

Treat your buddy how you want be treated.

Listen to your buddy.

If your buddy wants to help let them help.

Don't give up even if you and your buddy want to.

Stay on task the whole time.

Try your hardest.

Always be thankful that you have your buddy!

Have a lot of fun!

This data shows that already by the first week of school, students were identifying traits of a good buddy, and being empathetic to one another’s needs. By placing them in a situation where they had to rely on each other for help, students realized this responsibility early on, as seen through these buddy expectations.

The Co-Producer role was the most valuable for engaging kids in working together and encouraging improvement on a peer level, particularly during critique. For digital storytelling, the critique process became a valuable tool in shaping students' ability to share their stories with one another. Critique also provided an opportunity for students to express empathy for each other’s stories. We ran critique several times during the process, from reviewing digital story scripts, to their fine cut and final edits in the movie making process.

Building a Storytelling Community

The first few weeks were crucial in forming a strong classroom culture. It was the beginning of the year and I wanted to define a culture where students were encouraged to communicate and participate in the classroom community. I wanted them to be able to share aspects of themselves and who they are with one another. I tried many new strategies to engage students in building an empathetic community and hoped that it would encourage dialogue and a high level of comfort to share personal stories with each other. In my classroom, I wanted students to build a sense of identity through storytelling, be able to share their personal stories with each other, become empathetic to one another, and share these stories with the community.

Strategies for Building Community

In my previous years teaching in my multimedia lab, I’ve rearranged the seating several times to accommodate the different activities that students would be doing in the classroom. This year, my focus was making kids feel comfortable with the space, with me, and with each other.

- Circle of Chairs- “Everybody can see everybody’s faces.”-Lauren

Each day the students came in and sat in a circle. I didn’t dictate where they sat, but always made sure that everyone felt included in the circle and could see everyone. As a teacher, I felt like this configuration made me less like a “sage on the stage” and more of a facilitator of conversation and idea sharing. However, due to the loose seating assignments, students were extremely talkative which led to taking a longer time to settle in and quiet down. They often sat next to the people they were closest to in class, and as friendships changed, seating choices reflected those changes. After the semester ended, I invited a focus group of six students to share their thoughts and opinions on the semester. As a group, they felt that the circle provided a space to listen to directions or the agenda for the day, and that it helped people become more familiar with one another, especially in the beginning of the year. However, they agreed that starting every class period in the circle “took a long time to get people focused...and we lost a lot of our work time.”

- Feelings Drop Box- “This is a class where you talk about your feelings cause with the project that we did, we pretty much talked about our feelings.”-Tim

About two weeks into the semester, I hung a large clasped envelope on my desk where students could share notes with me about anything they were feeling. I introduced it as a place to leave thoughts and feelings for students who didn’t have a chance to share during our short class period. I wanted to encourage sharing in as many different contexts as possible in the classroom, by allowing students to express their feelings with me privately when they needed. I received notes about things happening in class with others, goings-on in life, and problems that the kids were experiencing. Some notes let me know if they were feeling sad or happy.

I learned later on in my focus group interview that I didn’t promote the box very well and that if I had, more students might have used it. However, as things came up I made sure I connected with the student the next day or at the end of class to check in and see how he or she was feeling. For instance, one student left a long letter to me explaining how her heart was broken knowing that her best friend was mad at her. Something had happened in their humanities class and the two girls stopped talking to each other. This was a difficult situation because they happened to be co-producing each other’s digital stories in my classroom. I sat the two girls down in my office and had them work out an agreement, and after a few days, they resolved their conflict. In contrast, one of my focus group students remarked that, “I never used that feeling box because it’s kind of my personal life my feelings. Sometimes I don’t want to express that to...a lot of people.”His remarks helped me understand that students felt differently about sharing.

- Tech Rovers-“When the tech rovers were there they were able to just help us with whatever we needed to do.”-Tim

In a technology classroom, I found it vital to the community to have students share their abilities and help in the classroom as a way to promote leadership, mentorship, accountability, and responsibility in students. The tech rovers system was magical! The kids had a spot on the whiteboard where they wrote their names so that others would know that they were available as tech rovers. At the start of class I would ask students if they wanted to be tech rovers, and those who wanted to help would add their names to the list. Every day and every class had volunteers, though some students volunteered some of the time, and some did not volunteer at all. In one of my focus group interviews, I found out that students who did not volunteer usually wanted to use all their time in class to work on their own project. One of my students felt she didn’t have enough computer skills to help, which was quickly shot down by another focus student who exclaimed, “I think she was amazing with the computer.” Students who did volunteer signed up because they felt like helping or finished their work early. They did not sign up if they felt people did not need their help.

I attempted to make sure I was requesting tech rovers to sign up for help in a variety of skills so that different students were able to contribute. Some examples of these expertise areas included Photoshop, creating a digital portfolio in Google Sites, editing in I-Movie, connecting to the school server, connecting a flash drive, connecting a digital camera, and general tech troubleshooting. I usually made a point in the beginning to ask for various special requests for students who felt comfortable in these areas. Although posting a variety of skills produced some changes in who signed up, it didn't keep a record that would have allowed me to show patterns and track student behavior.

- Computer Buddies/Co-Producers-“I enjoyed this project because I like to work with partners and I love to hear my voice...I also got help from my co-producer. He made sure I was on task.”-Kris

This buddy system was important to establish a sense of community and peer mentoring. I wanted to demonstrate that good projects could not be assessed without help and critique from another peer. Every student had a buddy who was responsible for offering kind, helpful, specific critique on their digital story throughout the production process. In my classroom, this buddy system was particularly conducive to the learning environment because we have a 2:1 computer ratio, and every student had to share their Mac G5 workstation with a buddy.

I also found that the buddy system helped keep students accountable to themselves and to others.Every student had a checklist of tasks that their buddy had to sign before they could go on to the next task. Before pairing students up as Co-Producers of digital stories, we did some initial computer skills building with a buddy of their choice. As part of this, I asked them to email me “Buddy Expectations” so that we could establish classroom standards for what we expected from each other. One of my focus students who didn’t always like sharing openly with the class surprisingly mentions sharing as part of his and his buddy’s expectations:

•Not to say things that are not TRUE.

•Work together.

•Be NICE to each other.

•Respect each other.

•Listen to each other.

•SHARE.

Another interesting model came from Tim and his partner:

Treat your buddy how you want be treated.

Listen to your buddy.

If your buddy wants to help let them help.

Don't give up even if you and your buddy want to.

Stay on task the whole time.

Try your hardest.

Always be thankful that you have your buddy!

Have a lot of fun!

This data shows that already by the first week of school, students were identifying traits of a good buddy, and being empathetic to one another’s needs. By placing them in a situation where they had to rely on each other for help, students realized this responsibility early on, as seen through these buddy expectations.

- Digital Story Critique-“I fell in love with it! The music was just right. The pictures were alive and well, wow! I would give it ten out of 13 firetrucks!”-Bill’s critique of Lauren's digital story

The Co-Producer role was the most valuable for engaging kids in working together and encouraging improvement on a peer level, particularly during critique. For digital storytelling, the critique process became a valuable tool in shaping students' ability to share their stories with one another. Critique also provided an opportunity for students to express empathy for each other’s stories. We ran critique several times during the process, from reviewing digital story scripts, to their fine cut and final edits in the movie making process.

Figure 3: A small group final draft script critique

According to reflection data, some students felt having a partner was one of the most fun or helpful parts of making the digital stories. I found that as a teacher, fostering these partnerships was vital to building a community that valued the feelings and voices of others. Screening the stories together and having a space for responding to each other's personal stories encouraged empathetic responses. As we screened final cuts, students frequently expressed empathy for one another through comments which started with “I can relate to your story because...” Each of the above strategies and choices helped us to build a community where students shared, were open with themselves, and empathetic to one another.

Pretext for Sharing our Stories

Before I began the project, I used the preliminary survey (Appendix A) data and some getting to know you activities to help me understand my students’ self-perceptions, comfort with sharing, and views on community.

On Identity:

95% of students in the 6th grade could define three words to describe themselves to someone new.

The most frequent words they chose varied from “fun”, “funny”, “awesome”, “creative”, “friendly” and “helpful.” I was intrigued by their choices as I learned who they were and how they identified themselves. I also noticed that their word choices showed empathetic tendencies by identifying as a “helpful” person.

47% of students said their stories would be found in the comedy section of a video store, whereas 6.5% said documentary.

I found this to be interesting since I expected that students would be more inclined to tell stories of their own lives. However, when I asked them this question I found that they focused on where they would want to find their story perhaps more than what the subject of the story would be.

I also had them all fill out an “Introducing Me” sheet (Appendix B) at the beginning of the year that would help me gauge what they were willing to share with me about themselves. They responded to questions such as, “What’s one thing I want you to know about me?” It was a great tool for getting to learn about my students at the beginning of the year.

On Sharing:

I evaluated how comfortable students were sharing with different groups. I had them rate how comfortable they were sharing their stories:

51.3% of students didn’t mind sharing their stories with their parents

44.9% couldn’t wait to share with their friends

35.8% didn’t mind sharing it publicly on the Internet.

In the age of YouTube, it interested me that they were not as comfortable sharing stories on the Internet as they were sharing with their friends, parents or other students. All students responded that they would want to share their stories, but some were more comfortable with different audiences. Students who did not feel comfortable sharing their stories were least comfortable sharing publicly on the Internet. Students who couldn’t wait to share their stories wanted to share most with friends, then with teachers, grandparents, parents, classmates, siblings, everyone, and least comfortable sharing publicly on the Internet. This data seemed to mirror the adolescent desire to develop peer relations. Not surprisingly, students most wanted to share with friends and are most comfortable sharing with friends.

On Community:

I wanted to gauge how students viewed themselves as part of a classroom community, and find out if they were engaged in the community outside of school. I wanted to foster a sense of community in my classroom through routines and structures that supported involvement and participation from the students. At this point I wanted to know if they felt like it was working.

86% of students feel they contribute to the classroom community.

86% of students feel they contribute to the greater San Diego community.

It struck me how many students felt they were a part of the classroom community. Although we had just begun school, students were already identifying themselves as “helpful,” “respectful,” “comfortable,” “safe,” “supportive,” and a “friend.” I definitely noticed that students were contributing to the classroom community by being helpful, respecting the technology, being a friend and volunteering to be a tech rover. One student described her contribution as, “Interacting with my classmates and even helping them with certain things.” It was good to know that they felt like the classroom was a place they could feel comfortable and where they felt they could be helpful. At this point, I felt comfortable knowing my students had a sense of what community felt like, looked like, and how they played a part in it.

Journey to Finding A Story

“I knew I had the story I wanted to tell when I started writing my script and thinking about what pictures to bring in, what I wanted my voice to sound like, etc.”-Chelsea

I found that many students experienced different pathways to telling the story they wanted to share. For some, the answer was clear, but for many, it was a winding path before arriving at the final screening. In the beginning, I knew it would be a challenge to facilitate the process of finding a story to tell, much less share with an audience. I wanted the story prompt to be open-ended, and have students guided by their own desire to share a story about their lives or someone else’s. I tried several approaches in my class to help students brainstorm stories to share. I also gave students several opportunities to share them as a way to build a culture of empathy in the classroom and increase their comfort with sharing. In this chapter, I describe some of the activities we engaged in to help students generate ideas for their stories.

After taking a course in my first year of graduate study in differentiation, I learned about a technique called “jigsaw.” The purpose of a jigsaw is to “develop a depth of knowledge not possible if the students were to try and learn all of the material on their own” (Aronsonet, 1978). I used the jigsaw technique to help students understand the elements of a digital story (Appendix C) Students broke out into a small group of four to watch one of the digital story examples I had compiled from various websites. After watching one together and answering questions about the story, students broke up into a second larger group of seven to discuss the different stories each had watched. After watching the stories and reflecting in large groups about what makes a digital story, we created a list of elements of a digital story as a class. Students described that a digital story had to have pictures, music, voiceover, titles, effects, and transitions. Although we had not pulled out themes as a class, I hoped this activity helped students frame in their minds the kinds of stories people were telling and the variety of stories to tell.

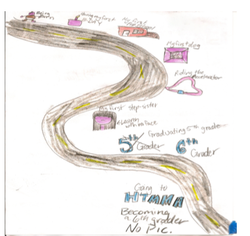

I found the life road map activity (Appendix D) as a result of a web search to help students reflect on their lives through the metaphor of a journey on a road. I wanted students to remember significant moments in their lives, and attribute those to the bigger picture on the map of life. In asking students to reflect on their lives in this way, I found it opened students up to expressing not only the memories of what had happened in their lives, but also triggered an emotional response to those moments. The activity was a two-fold process where students had to list significant events in their lives according to what kind of road symbol they represented such as speed bumps, stop signs, traffic lights, detours and dead ends. Then, they had to take those moments and illustrate a map showing the symbols and events as a road. There were many different interpretations of what made an event a stop sign or a speed bump. The drawing of the map was also left very open as a free interpretation. I found that this activity helped students most in processing the meaning of a significant life event, and helped them recall these events as moments in their journey of life.

According to reflection data, some students felt having a partner was one of the most fun or helpful parts of making the digital stories. I found that as a teacher, fostering these partnerships was vital to building a community that valued the feelings and voices of others. Screening the stories together and having a space for responding to each other's personal stories encouraged empathetic responses. As we screened final cuts, students frequently expressed empathy for one another through comments which started with “I can relate to your story because...” Each of the above strategies and choices helped us to build a community where students shared, were open with themselves, and empathetic to one another.

Pretext for Sharing our Stories

Before I began the project, I used the preliminary survey (Appendix A) data and some getting to know you activities to help me understand my students’ self-perceptions, comfort with sharing, and views on community.

On Identity:

95% of students in the 6th grade could define three words to describe themselves to someone new.

The most frequent words they chose varied from “fun”, “funny”, “awesome”, “creative”, “friendly” and “helpful.” I was intrigued by their choices as I learned who they were and how they identified themselves. I also noticed that their word choices showed empathetic tendencies by identifying as a “helpful” person.

47% of students said their stories would be found in the comedy section of a video store, whereas 6.5% said documentary.

I found this to be interesting since I expected that students would be more inclined to tell stories of their own lives. However, when I asked them this question I found that they focused on where they would want to find their story perhaps more than what the subject of the story would be.

I also had them all fill out an “Introducing Me” sheet (Appendix B) at the beginning of the year that would help me gauge what they were willing to share with me about themselves. They responded to questions such as, “What’s one thing I want you to know about me?” It was a great tool for getting to learn about my students at the beginning of the year.

On Sharing:

I evaluated how comfortable students were sharing with different groups. I had them rate how comfortable they were sharing their stories:

51.3% of students didn’t mind sharing their stories with their parents

44.9% couldn’t wait to share with their friends

35.8% didn’t mind sharing it publicly on the Internet.

In the age of YouTube, it interested me that they were not as comfortable sharing stories on the Internet as they were sharing with their friends, parents or other students. All students responded that they would want to share their stories, but some were more comfortable with different audiences. Students who did not feel comfortable sharing their stories were least comfortable sharing publicly on the Internet. Students who couldn’t wait to share their stories wanted to share most with friends, then with teachers, grandparents, parents, classmates, siblings, everyone, and least comfortable sharing publicly on the Internet. This data seemed to mirror the adolescent desire to develop peer relations. Not surprisingly, students most wanted to share with friends and are most comfortable sharing with friends.

On Community:

I wanted to gauge how students viewed themselves as part of a classroom community, and find out if they were engaged in the community outside of school. I wanted to foster a sense of community in my classroom through routines and structures that supported involvement and participation from the students. At this point I wanted to know if they felt like it was working.

86% of students feel they contribute to the classroom community.

86% of students feel they contribute to the greater San Diego community.

It struck me how many students felt they were a part of the classroom community. Although we had just begun school, students were already identifying themselves as “helpful,” “respectful,” “comfortable,” “safe,” “supportive,” and a “friend.” I definitely noticed that students were contributing to the classroom community by being helpful, respecting the technology, being a friend and volunteering to be a tech rover. One student described her contribution as, “Interacting with my classmates and even helping them with certain things.” It was good to know that they felt like the classroom was a place they could feel comfortable and where they felt they could be helpful. At this point, I felt comfortable knowing my students had a sense of what community felt like, looked like, and how they played a part in it.

Journey to Finding A Story

“I knew I had the story I wanted to tell when I started writing my script and thinking about what pictures to bring in, what I wanted my voice to sound like, etc.”-Chelsea

I found that many students experienced different pathways to telling the story they wanted to share. For some, the answer was clear, but for many, it was a winding path before arriving at the final screening. In the beginning, I knew it would be a challenge to facilitate the process of finding a story to tell, much less share with an audience. I wanted the story prompt to be open-ended, and have students guided by their own desire to share a story about their lives or someone else’s. I tried several approaches in my class to help students brainstorm stories to share. I also gave students several opportunities to share them as a way to build a culture of empathy in the classroom and increase their comfort with sharing. In this chapter, I describe some of the activities we engaged in to help students generate ideas for their stories.

- Jigsaw

After taking a course in my first year of graduate study in differentiation, I learned about a technique called “jigsaw.” The purpose of a jigsaw is to “develop a depth of knowledge not possible if the students were to try and learn all of the material on their own” (Aronsonet, 1978). I used the jigsaw technique to help students understand the elements of a digital story (Appendix C) Students broke out into a small group of four to watch one of the digital story examples I had compiled from various websites. After watching one together and answering questions about the story, students broke up into a second larger group of seven to discuss the different stories each had watched. After watching the stories and reflecting in large groups about what makes a digital story, we created a list of elements of a digital story as a class. Students described that a digital story had to have pictures, music, voiceover, titles, effects, and transitions. Although we had not pulled out themes as a class, I hoped this activity helped students frame in their minds the kinds of stories people were telling and the variety of stories to tell.

- Life Road map

I found the life road map activity (Appendix D) as a result of a web search to help students reflect on their lives through the metaphor of a journey on a road. I wanted students to remember significant moments in their lives, and attribute those to the bigger picture on the map of life. In asking students to reflect on their lives in this way, I found it opened students up to expressing not only the memories of what had happened in their lives, but also triggered an emotional response to those moments. The activity was a two-fold process where students had to list significant events in their lives according to what kind of road symbol they represented such as speed bumps, stop signs, traffic lights, detours and dead ends. Then, they had to take those moments and illustrate a map showing the symbols and events as a road. There were many different interpretations of what made an event a stop sign or a speed bump. The drawing of the map was also left very open as a free interpretation. I found that this activity helped students most in processing the meaning of a significant life event, and helped them recall these events as moments in their journey of life.

Figure 4 - Lauren’s Life Road Map

The activity also helped students learn about each other as they shared them in a gallery walk. A gallery walk is a forum for sharing student work, where students look at each other’s work and leave kind, helpful, or specific comments about it. The day we set up gallery walk, we wrote down a list of gallery walk norms ranging from taking our time and leaving good feedback, to being kind and being thoughtful. I played soft music in the background to inspire a gallery feel, as students went around to different tables around the room and reviewed their classmates’ life road maps. On sticky notes, students left comments sharing what they liked about the work of others. They felt that the gallery walk was a good way to see each other’s work and learn about their lives. In an exit card following the activity, I asked students to comment on the following questions:

1) How did you feel about the life road map activity?

What was the most interesting life road map that made you want to know more? Why?

Find a comparison you found between your life road map and someone else’s.

Find one difference.

Where would you like to see your life road go in the future?

Students responded to the first question positively overall:

“I loved it!”

“I feel really good because I don’t mind people knowing my life.”

“I felt very comfortable writing my road life because I felt like sharing it.”

Many students shared these sentiments of feeling comfortable sharing with others, while other students expressed a desire to reflect and express themselves. One student felt “really nice about it because I was expressing my feelings about the past.” Another remarked, “It felt good because after it brought back good memories to share. Before I felt nervous because in the beginning I didn’t know how people will react.”

However, a few students were not comfortable sharing their road maps with the class. For a handful of students, they felt their maps were too personal to share with others in a gallery walk or they felt uncomfortable sharing what they created. In my feelings drop box, I received one note from a girl who was “embarrassed” to share her life road map because it was “too personal.” In allowing students the option before the gallery walk to not share their maps, I hoped that they would soon feel comfortable sharing over time.

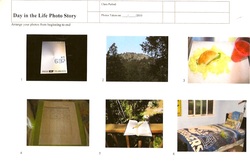

The day in the life photo project was one I came up with to help students relate their stories in a visual way using photography (Appendix E). Because the final digital stories would be made up of at least some personal photographs, I wanted students to be familiar with the camera and be able to construct a mini-story about a day in their lives in six photos. The purpose of the assignment was to tell a story without words--a skill called visual storytelling that would later become an essential part of their final digital story. The result was a series of selected photos on a storyboard with no text, so as not to identify the storyteller. These were hung up in our room for students to look at and speculate which pictures belonged to whom. Unfortunately, I ran out of time and could do nothing more than assign it as a homework. We didn’t share the day in the life photo stories as a class as I had intended.

The activity also helped students learn about each other as they shared them in a gallery walk. A gallery walk is a forum for sharing student work, where students look at each other’s work and leave kind, helpful, or specific comments about it. The day we set up gallery walk, we wrote down a list of gallery walk norms ranging from taking our time and leaving good feedback, to being kind and being thoughtful. I played soft music in the background to inspire a gallery feel, as students went around to different tables around the room and reviewed their classmates’ life road maps. On sticky notes, students left comments sharing what they liked about the work of others. They felt that the gallery walk was a good way to see each other’s work and learn about their lives. In an exit card following the activity, I asked students to comment on the following questions:

1) How did you feel about the life road map activity?

What was the most interesting life road map that made you want to know more? Why?

Find a comparison you found between your life road map and someone else’s.

Find one difference.

Where would you like to see your life road go in the future?

Students responded to the first question positively overall:

“I loved it!”

“I feel really good because I don’t mind people knowing my life.”

“I felt very comfortable writing my road life because I felt like sharing it.”

Many students shared these sentiments of feeling comfortable sharing with others, while other students expressed a desire to reflect and express themselves. One student felt “really nice about it because I was expressing my feelings about the past.” Another remarked, “It felt good because after it brought back good memories to share. Before I felt nervous because in the beginning I didn’t know how people will react.”

However, a few students were not comfortable sharing their road maps with the class. For a handful of students, they felt their maps were too personal to share with others in a gallery walk or they felt uncomfortable sharing what they created. In my feelings drop box, I received one note from a girl who was “embarrassed” to share her life road map because it was “too personal.” In allowing students the option before the gallery walk to not share their maps, I hoped that they would soon feel comfortable sharing over time.

- Day in the Life Photo Project

The day in the life photo project was one I came up with to help students relate their stories in a visual way using photography (Appendix E). Because the final digital stories would be made up of at least some personal photographs, I wanted students to be familiar with the camera and be able to construct a mini-story about a day in their lives in six photos. The purpose of the assignment was to tell a story without words--a skill called visual storytelling that would later become an essential part of their final digital story. The result was a series of selected photos on a storyboard with no text, so as not to identify the storyteller. These were hung up in our room for students to look at and speculate which pictures belonged to whom. Unfortunately, I ran out of time and could do nothing more than assign it as a homework. We didn’t share the day in the life photo stories as a class as I had intended.

Figure 5. Student Work Sample: Day in the Life Photo story

After a few weeks of engaging the students in these activities, the time came for them to submit their initial ideas about what story they wanted to share as a digital story. I sent out a series of surveys in Google Forms, asking them questions about who they wanted to tell the story about, who the story was for, why they wanted to tell that story, and what they wanted to send as a message to others through their story. I spent weeks asking the same questions, and re-phrasing those questions as I helped students through this most difficult task in the whole process. One student reflected that the most difficult part of making a digital story is “finding the right story to tell because you want to share a lesson with everyone.” These surveys ended up being my primary source of getting at the question continually on my mind: What stories do kids want to tell?

In response to my own sense that students weren’t telling the stories they wanted or needed to tell, I sent out a digging deeper survey two weeks later, asking them what they would gain personally from their stories, what others will gain, and if they could change their story what story would they want to tell. Out of 22 students who responded, nine students didn’t want to change their story, and 13 students offered new stories. From this data, I started having individual conversations with students whose new stories presented a deeper sense of personal need to tell.

I wanted kids to articulate why they wanted to share their particular stories and what others might gain from their story, hoping that this would help them discover a purpose for sharing. I wanted them to identify a strong story, so that their digital story would not be flat. This corresponds to Banaszewski's advice that the “technology was always secondary to the storytelling”(2002, p.35). Ohler also states the importance of “story first” (2006, p.4). Finally students had chosen their final story concepts to turn into scripts.

We went on to do a voiceover recording of the scripts, which was a real turning point in the project. I had the opportunity to bring in a voice actor to describe the process and help me with the recording of the stories. Hearing the voices of the students reading their stories transformed the words into context for me. I felt the power of the stories that the kids had to tell through their voices. With expert help, students were getting a great experience, dramatizing their life stories through their own voice. It was a magical transformation that made the words leap off the page. The process was finally underway, and the digitizing of the stories began.

From the voiceover phase, students began to insert images into I-Movie and edit together voice and pictures. I sent another survey to have students reflect on their final choices and give me an indicator of how the process was going for them. I asked the following questions:

As a producer, what message do you want to communicate to everyone who watches your story?

If you were talking to another student, what would you say is the most difficult/fun part of the process?

If you could change anything about the process so far, what aspect would you change and why?

What else can you say about digital storytelling so far?

Their responses helped me further understand what they hoped for their stories to communicate, and describe the most fun and most difficult parts of the process. When I analyzed the data, students overall found that the most difficult part of the process was voiceover recording and finding pictures to tell the story. Editing in I-Movie and putting the pictures into the story was the most fun part according to most students. This data reflects the perceptions that I found out later in my multimedia exit survey. Most students claimed that learning to use I-Movie was their favorite part of the project, and for many, their favorite part about the class.

It became my primary goal to help students find the story they most wanted to tell and share with everyone. Yet, I learned from my focus group interview after our project had ended that if I had simply asked students to tell a personal story, this process could have been much easier and clearer. Students were confused by my open-ended questioning. I asked them who they wanted to tell a story about, rather than what story they wanted to tell. I gave students the option to tell the story of their defining moment from their Humanities assignment or to tell a different story that they wanted to share. At this point it became tricky, since students wanted to tell a range of stories that involved different levels of vulnerability. In addition, I had to find a way to support the development of different types of scripts, since their Humanities class was focusing on defining moments alone. I also realized the importance of supporting students in telling the stories that they really wanted to tell; for some these were deep stories that served an emotional need, while for others, the stories were seemingly more surface.

The Stories Kids Want to Tell

“You really want to pick something that you really want to show with everyone else, not just do it to do it, because you want to be able to be proud of it.”-Tim

The 6th grade class produced a wide-range of digital stories all having a personal connection to their own lives. In my focus class, many themes came from a writing assignment in their humanities class where they shared a defining moment in their lives. For many that moment was defined by new friendship, lost friendship, divorce, death, or achievement. In the scriptwriting process, students were asked if they wanted to tell a digital story from their defining moment or if they had another story they wished to tell. Surprisingly, out of 27 defining moment stories, 5 students used their defining moment writing piece and 17 changed their stories. One student changed his story 3 times, while most others who changed their story only did so once.

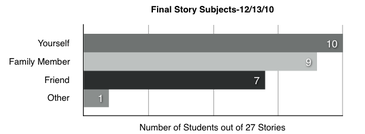

In the process of looking for what stories kids want to tell, I asked them who they wanted to tell a story about. Initially, most students wanted to tell a story about themselves or a friend. Family members came up last. However, when I compare this preliminary data with the stories they ended up telling, students told stories mostly about themselves, family, friends and least of all “other.” The graph shows the distribution of the number of students who chose a particular story subject:

- Choosing the Story

After a few weeks of engaging the students in these activities, the time came for them to submit their initial ideas about what story they wanted to share as a digital story. I sent out a series of surveys in Google Forms, asking them questions about who they wanted to tell the story about, who the story was for, why they wanted to tell that story, and what they wanted to send as a message to others through their story. I spent weeks asking the same questions, and re-phrasing those questions as I helped students through this most difficult task in the whole process. One student reflected that the most difficult part of making a digital story is “finding the right story to tell because you want to share a lesson with everyone.” These surveys ended up being my primary source of getting at the question continually on my mind: What stories do kids want to tell?

In response to my own sense that students weren’t telling the stories they wanted or needed to tell, I sent out a digging deeper survey two weeks later, asking them what they would gain personally from their stories, what others will gain, and if they could change their story what story would they want to tell. Out of 22 students who responded, nine students didn’t want to change their story, and 13 students offered new stories. From this data, I started having individual conversations with students whose new stories presented a deeper sense of personal need to tell.

I wanted kids to articulate why they wanted to share their particular stories and what others might gain from their story, hoping that this would help them discover a purpose for sharing. I wanted them to identify a strong story, so that their digital story would not be flat. This corresponds to Banaszewski's advice that the “technology was always secondary to the storytelling”(2002, p.35). Ohler also states the importance of “story first” (2006, p.4). Finally students had chosen their final story concepts to turn into scripts.

We went on to do a voiceover recording of the scripts, which was a real turning point in the project. I had the opportunity to bring in a voice actor to describe the process and help me with the recording of the stories. Hearing the voices of the students reading their stories transformed the words into context for me. I felt the power of the stories that the kids had to tell through their voices. With expert help, students were getting a great experience, dramatizing their life stories through their own voice. It was a magical transformation that made the words leap off the page. The process was finally underway, and the digitizing of the stories began.

From the voiceover phase, students began to insert images into I-Movie and edit together voice and pictures. I sent another survey to have students reflect on their final choices and give me an indicator of how the process was going for them. I asked the following questions:

As a producer, what message do you want to communicate to everyone who watches your story?

If you were talking to another student, what would you say is the most difficult/fun part of the process?

If you could change anything about the process so far, what aspect would you change and why?

What else can you say about digital storytelling so far?

Their responses helped me further understand what they hoped for their stories to communicate, and describe the most fun and most difficult parts of the process. When I analyzed the data, students overall found that the most difficult part of the process was voiceover recording and finding pictures to tell the story. Editing in I-Movie and putting the pictures into the story was the most fun part according to most students. This data reflects the perceptions that I found out later in my multimedia exit survey. Most students claimed that learning to use I-Movie was their favorite part of the project, and for many, their favorite part about the class.

It became my primary goal to help students find the story they most wanted to tell and share with everyone. Yet, I learned from my focus group interview after our project had ended that if I had simply asked students to tell a personal story, this process could have been much easier and clearer. Students were confused by my open-ended questioning. I asked them who they wanted to tell a story about, rather than what story they wanted to tell. I gave students the option to tell the story of their defining moment from their Humanities assignment or to tell a different story that they wanted to share. At this point it became tricky, since students wanted to tell a range of stories that involved different levels of vulnerability. In addition, I had to find a way to support the development of different types of scripts, since their Humanities class was focusing on defining moments alone. I also realized the importance of supporting students in telling the stories that they really wanted to tell; for some these were deep stories that served an emotional need, while for others, the stories were seemingly more surface.

The Stories Kids Want to Tell

“You really want to pick something that you really want to show with everyone else, not just do it to do it, because you want to be able to be proud of it.”-Tim

The 6th grade class produced a wide-range of digital stories all having a personal connection to their own lives. In my focus class, many themes came from a writing assignment in their humanities class where they shared a defining moment in their lives. For many that moment was defined by new friendship, lost friendship, divorce, death, or achievement. In the scriptwriting process, students were asked if they wanted to tell a digital story from their defining moment or if they had another story they wished to tell. Surprisingly, out of 27 defining moment stories, 5 students used their defining moment writing piece and 17 changed their stories. One student changed his story 3 times, while most others who changed their story only did so once.

In the process of looking for what stories kids want to tell, I asked them who they wanted to tell a story about. Initially, most students wanted to tell a story about themselves or a friend. Family members came up last. However, when I compare this preliminary data with the stories they ended up telling, students told stories mostly about themselves, family, friends and least of all “other.” The graph shows the distribution of the number of students who chose a particular story subject:

Figure 6. Subjects of student stories at final draft

Although I find it interesting to see a change over time regarding the subject matter of the students’ stories, what this data doesn’t show is how the stories intertwined subjects and the resulting themes that emerged. Stories of themselves were really about moments in their lives that either represented personal goals, dreams, accomplishments, defining moments, or experiences. Stories about family members were about their dealing with the death of a family member, experiencing divorce, learning about family roots, remembering a time spent with family, welcoming new family members, and saying goodbye to college-bound siblings. Stories about friends were about loss, moving on, best friends, and the importance of friends. The outlier story about the high school robotics team could cross over into family since the inspiration came from a sibling on the team, however, I kept it as a separate category due to the nature of the storytelling, which leaned more towards documentary than personal narrative.

I wanted to discern what students hoped to gain by sharing their stories. Students wanted to share stories for a variety of reasons. They wanted to know more about themselves, or gain knowledge about others. They wanted to gain trust, or learn to let go. They wanted to tell stories about dreams, happiness, memories, and defining moments. They wanted to let others know that it’s important to move on, to recognize that people pass away, to not get down. They wanted to tell stories about the importance of friends. They wanted to raise awareness, or share an experience. In asking what they hoped to gain through telling their story, students had different personal reasons that they communicated:

These are just some of the lessons they wanted to share and messages they wanted to communicate:

These lessons and messages not only communicate the heart of their stories, but also show how many aspects of life they tackled. From sharing their learning, their hardships, their successes, their memories, and their interests, students shared a voice mature beyond their years.

In interpreting and internalizing these stories, I have come to find that:

A) Every student has a story to share, and different stories serve different purposes

B) Sharing personal stories is scary, but it doesn’t have to be

C) The more personal the story, the greater the impact it can have on the storyteller and the audience

I wanted to understand student thinking on a deeper and more personal level as it applied to the themes that emerged. Every student approached the storytelling process differently and as a result had a different experience and point of view to share. As I wondered what happened during the project, I realized that my insight would be inspired by a select group of focus students who represented a wide range of outcomes regarding the stories they wanted to tell and the impacts of their stories.

Some Storytelling Cases

I chose three case studies to highlight some of the details around what kids were feeling and thinking during the digital storytelling project. Since I cannot go into depth on each individual student in my focus class, I selected the following students to represent the variety of approaches that students took in making a digital story and the stories they wanted to tell. Each case shares the experience of one student, however, their perspectives are shared by others in the class. I hope that the cases reveal the importance of giving students voice, allowing change, understanding comfort levels, and listening to what stories your students want to tell. I examined their reasons for sharing or not sharing personal stories. I found connections they made with others who were affected by their stories. I learned the impacts their stories had on themselves and others.

Sending a Message: Samantha’s Story

“Well, for me, I really wanted to tell this story, because I really want to get it off my back. My mother and grandma are still grieving about it making it hard for me.”

Samantha wrote about the grandfather she never knew as part of her initial defining moment writing piece in Humanities. She had a direct purpose in telling her story. She needed to get something off her chest. It had been bothering her to know that her mother and Grandmother were suffering still from grief over his death two years before Samantha was born. In her script she writes:

All my life I have been grieving for someone who died 14 years ago.You would probably think that this person has nothing to do with me but it’s in my name.... This person is my Grandfather Roy and I am named after him, ... so my very existence is constantly reminding people of him.

Samantha knew from the first initial survey whose story she wanted to tell and why. She held on to this intent throughout the process and she hoped to communicate to others through her story, “That even though you are sad you have to move on.” Her story led her to question who the man was that her family mourned. It determined her approach to finding her own answers and looking through family archives to get them, and it led to her own conclusion that her family needed to celebrate his life and move on. Her purpose in telling her story came across in the end of her script:

It is quite sickening to an 11 year old girl to say that her deceased grandfather is ruining her life but it is true because of all the sadness he has brought to me and my family.

In sharing her story, Samantha made a powerful impression on her family. In an interview recorded a month after the exhibition, the first time students shared their stories with family, Samantha’s mother shared her perspective on what she thought of the story and her surprise in seeing it for the first time:

“I actually broke out in tears during the presentation. I..I didn’t know what she was doing with them [the pictures] and why... she never got to meet my dad. And hers was based on 14 years ago although she’s only 11, that 14 years ago was a day that changed her life. And it threw me. It threw my husband who was sitting there watching it, just like ‘Oh My Gosh’ because of the stories she’s heard and that’s how she expresses it about this man who was her namesake.”

She went on to share with Samantha that her grandmother watched the story at her home and afterward said of Samantha, “What a deep, kind passionate thinker.” For Samantha as a digital storyteller, the impact was strong. In her final reflection, she felt that a big take-away from the project was “hearing my mom say that my grandmother saw my movie.” During the process, she described, “I’ve been learning more about myself and my grandfather as I’ve been doing it.”

Samantha's approach, with a clear intent and expected outcome, led to her telling a story which in the end made her “proud.” It also elicited empathy from those who saw it. Before screening her story at exhibition, the story made an important impact on another student in her class. This is what he had to share after watching her story,

“I connect with this story a lot because I never got to meet my grandfather either and his name is [same name as student]...so try and forget that.”

Although the tone of the statement doesn’t come across, in the video showing this response during a critique session, the student was trying to empathize by saying he felt what Samantha was feeling by constantly living with the reminder of his own namesake.

For Samantha, the digital story provided a vehicle to address a nagging need to share a dilemma in her life. She was trying to resolve an issue she had been dealing with for awhile and send a message to her family and to others about the way it made her feel. In a focus group interview, she stated, “I think the digital story helped me. I’d do it again if I had a story to tell.” The power of the digital story for her not only affected her own sense of getting something off her chest, but also made an impact on her family members who didn’t have a full sense of what Samantha was feeling. I asked Samantha later on if things had changed at home as a result, and if her family had stopped bringing up the pain of their grief. She told me that “things were better.”

Another interesting point about Samantha’s case was that she never felt like she couldn’t share her story. Although she admitted to being a little scared to share, it was to her the only story she could think to tell. She reflected, “I just had to kind of jump and say I’m just going to do a personal story. And I did and it turned out good.”

Samantha's approach of jumping in to tell a personal story resonated with the approach of other students. However, even for students with a clear need or desire to tell a personal story, sharing those stories didn’t always come easily.

Finding her Voice and Helping Others: Lauren’s Story

“You pushed me a little harder than everyone else...I felt like you were pushing me to tell an amazing story. And when I did, I felt it could be better but everything has room for improvement...You sat me down to write down thoughts of the stories I wanted to write.”

Lauren was my advisee, a student who I met with three times a week, and whose home and family I had visited. When she came to me with her idea to tell a rollercoaster story, I felt like she had something much more meaningful to share. It came from her very first draft. I noted that there was a quick reference to her mother’s divorce and her new family. I pushed her to develop that part of it more. I could tell it was there, hiding underneath the surface.

At about the same time, I sent a survey asking students if they could change the story they had set out to tell, what would they change it to and why. Lauren responded. “If I could change my story to my mom getting remarried because that was a happy moment in time for her. I wouldn’t talk about her divorce because the main details are the details my mom doesn’t want anybody else to hear or know.” Although I tried not to be critical of students' choices and direct their intentions, I still found it necessary to push some kids thinking when I saw that there was a potential for a deeper story. I asked Lauren probing questions about what had happened.

As a result, Lauren changed the structure of her story to tell her “Up and Down Life.” The simple way she shared these moments in her life communicated a complex understanding of hardships contrasting with joy, as shown in this excerpt from her script:

Have you ever had an up and down life like mine? Well, if you have then you can probably relate to this story. If not then follow along and you’ll be able to feel my up and down life.

UP- I am an eleven year old girl living in San Diego, CA and LOVING IT!

DOWN- On my birthday when I was seven years old my parents got divorced. I only got one present that year.

It came together in a way that she and her family were proud of and it allowed Lauren to open up a part of herself that “some people don’t know about me.” Her original intent to teach people about her life was preserved, but her story changed to reflect who she was and what she had been through. Her case represented the importance of helping students recognize elements of their stories that they are not as comfortable sharing, but that are important to them. Her story also helped another student share personal feelings he hadn’t been ready to expose.

I asked John, one of my focus students, about a story he shared at the beginning of school. It was a personal story about a friend who was special to him but had gone to jail. I asked him why he did not want to make his digital story about his friend and he told me it was too personal. He had many memories with his friend, and explained how he had pictures of them together. I encouraged him to look further into why that story wasn’t one he could tell. It came back to the fact that he didn’t want to share the whole story because it was personal.

At that moment, Lauren walked in on our conversation. She and I had the same conversation a couple of weeks earlier about personal things we share and our comfort levels when sharing those with others. I had her talk to him about how she and I discussed the same difficulty of opening up the parts of the story that are difficult or personal. The conversation blossomed and I soon found myself just listening as they spoke to each other about reasons why they were wanting to share parts of themselves without giving away the whole story. Here are a few things I heard them say:

“I wanted to tell my story because no one knows me better than myself”

“Our parents can’t get inside our heads and know our thoughts.”

“You have to let some of you out and not be shy because you can’t hold it all in, you have to let some things out.”

“It’s good to let people know who you are.”

Through this conversation, John had found a confidante. When I asked him if he’d like to try and write another script, he said he would and Lauren asked if she could read it. He left knowing that he could share a personal story without giving too much of himself up. Lauren empathized and was able to help him feel comfortable opening up because of the success in having done so herself! It was a powerful moment in the storytelling process because empathy between the students helped open up a new pathway for a student who was struggling to tell his story. They learned through each other’s experiences to relate to one another, and gained the courage to share.

Lauren taught me that the stories that kids want to tell might be hiding underneath the surface. With conversation, probing questions, and support, some students might have felt more comfortable sharing. By pushing herself to be more honest with her feelings, she stated,

“To me, I thought that the deep and personal stories might have got the most applause because that means you put your heart into your story.” When I asked her why she was able to share a more personal account of her story, she explained, “I didn’t really want to share this topic, because I thought it was too revealing, but I did because some people don’t know that about me.” In the end, after screening her story, she felt proud because “my family members were very proud of me.” Some students felt like pushing themselves to new limits. In Lauren’s case, she soared to new limits, and helped not only herself, but others, to go deeper.

Opening up the Past: Shelly’s Story

“I think that the choices I made was just how important the story was for me.”

Similar to Lauren’s case, Shelly changed her original story about her first sleepover with friends. When I asked the question, “If you could change your story, what story would you want to tell?” Shelly replied:

“If I had to change my story I would probably write about my brothers death. I would write about that because it was important to me and it helped me move on and be stronger. It also taught me that we all have things in life that we don’t like but we can't forget about.”

Not many students had such powerful alternative stories to share that it compelled me to ask them if they’d change it. However, I asked Shelly if she wanted to share the story of her brother. Unlike Lauren, I did not have to coach the story out of her. She asked me if it was okay to tell the story of her brother, as if she wasn’t sure that I’d accept it. I told her absolutely it was okay and that I appreciated her willingness to share his story with us.

This was a critical moment that led to a story that became by far one of the most memorable in the whole process. I realized at that moment, that if had I not asked that question, she would not have had the chance to share a deeply personal story and affect us all. This experience taught me that sharing stories is a personal process, and it requires every opportunity to reflect. Asking students multiple times about the story they want to tell helps determine if it is the one they most wish to share.

These cases taught me how to view the approaches of each student with the intent to help them share a story that they will be proud of, that they want to share, and that has meaning for themselves and others. I learned that these students all experienced varying levels of success on the project, and personal fulfillment. Their journeys to finding their stories were complex and motivated by different reasons. I realized that although students all have a story to share, their desire to share will be different. The power of digital storytelling was in the heart of the stories kids want to tell, and their desire to share fueled the impact their stories would have.

Screening and Sharing the Stories

“I want to tell something I am comfortable with that way I can go deep into that and not get too personal” -Lauren

“I felt proud and shy because it was really personal.”-Colby

It was important to keep in mind student comfort levels when sharing personal aspects of their lives with each other. Before we began the storytelling process, I shared my story of being adopted from Korea. I returned to Korea for the first time at age 23 for an educational trip and discovered a sense of Korean identity I hadn’t known before. I also shared other digital stories with students that included stories about identity, loss of a family member, celebrating cultural heritage, overcoming adversity, and a defining moment of a veteran. Looking back, I realized that many of the stories I shared as models were deeply personal, reflecting both positive and negative experiences. I assumed that in order for students to experience a positive personal impact from the process, they would need to tell a personal story. However, as Colby's words above highlight, the more personal the story, the more risky it feels to share.

When it finally came down to exhibition night, excitement and terror mixed in the air as I asked students how they wished to exhibit their digital stories. I got mixed reviews. Some students wanted to share it on a computer with just a few select people, while others wanted it projected on the big screen with a movie theater audience, popcorn and awards. Remember, I was only one teacher with 112 sixth graders and one night to invite the entire 6th grade class and families.

I decided to compromise with my students and host four screenings in one night by class, inviting parents and guests to attend their students’ class screening. Students were encouraged to participate and present their digital stories, however, not everyone shared that night. The majority seemed to be pleased with my compromise since they didn’t have to share with the whole 6th grade and were comfortable at that point sharing with their class.

I didn’t realize until after collecting their reflections on the project what an impact this decision would have on the entire project. I struggled with the decision because I wanted to honor the students individually but couldn’t quite come up with a better way. I found that sharing the stories with an audience of family and classmates led to unexpected results. Students who were at first afraid to share, were mostly glad that they did. I asked students how they felt when their movie ended and they heard the audience applause. 18 out of 21 students responded to this reflection question positively, using words like “proud,” “happy” and “relieved.”

On the other hand, some students felt “upset,” “nervous,” “shy,” and “uncomfortable.” Samantha claimed she “felt happy that I was able to show my movie. It was really nice.” In response to what others said about her movie, she wrote, “My mom and dad said that they cried.” For Samantha her storytelling journey had a direct impact on her family members. Sharing her story helped her communicate a message further validated by her own family's reactions. Her mother revealed to us that she shared the story with her grandmother, who also cried and was glad to have it. The effects went far beyond Samantha’s expectations.

Shelly exclaimed, “I was happy and overjoyed that people actually liked it...I know that it touched some people and thats what I wanted...I felt happy and I smiled.” When she went on to write what other people had to say about her story, she continued, “People said that it was really powerful, touching, and a lot of people cried. They also said that it was an amazing and awesome movie and it was really cool." The impact of sharing produced the desired outcomes for Shelly and though she didn’t mention it in her comment, I would guess that her story would not have had the same impact on her or her audience had she stuck with her original idea.

Screening the movies was the defining moment of the whole project for me. It was in this moment that my goal to have students share themselves with the community through digital storytelling came alive and in working together, we achieved the seemingly impossible task of sharing our stories with others. By giving the students an opportunity to express their individuality and creativity with a real world audience through an exhibition night, I found that in the end making and sharing the stories was well worth the effort.

In my quest to have students share and build their identities, be more empathetic, and belong to a community of storytellers, I’ve found that students became more comfortable sharing with others. Students shared stories that were personal on many different levels, and our classroom community made it all possible. Students wrote a reflection at the end of the project and described one take away from the experience:

When I asked students if they would want to tell another story using digital storytelling, 19 out of 21 had an idea of a story that they would want to tell. This data encouraged me that at the end of the project students hadn’t given up on the idea that they could tell stories using this new method. Even as the school year comes to a close, I have had students asking for help on digital stories they’ve made for family outside of school. Since the project, many students have come up to tell me that they have begun or have already made another story for a family member to give as a gift. Shelly made DVDs for her mom to share at her workplace. Samantha accomplished her goal and her mother shared her story with her grandparents. Another student made a story for her Bat Mitzvah.

There are still unanswered questions. How can I help all students feel safe to share a personal story with others? How I can preempt any negative behavior that could jeopardize sharing? How can I make the project expectations more defined? How can I better assist students with finding a personal story to tell?

Now that I have completed the same project with a class of 8th graders, I have learned that older students are more ready to share a personal story. Although many parts of the process were similar to the 6th graders, I was able to structure a more direct and efficient approach to finding a story. I’ve learned to value what’s important in the process, and in my conclusions I highlight three themes that I took away from the project to illustrate what happened when I used digital storytelling in my classroom.

Although I find it interesting to see a change over time regarding the subject matter of the students’ stories, what this data doesn’t show is how the stories intertwined subjects and the resulting themes that emerged. Stories of themselves were really about moments in their lives that either represented personal goals, dreams, accomplishments, defining moments, or experiences. Stories about family members were about their dealing with the death of a family member, experiencing divorce, learning about family roots, remembering a time spent with family, welcoming new family members, and saying goodbye to college-bound siblings. Stories about friends were about loss, moving on, best friends, and the importance of friends. The outlier story about the high school robotics team could cross over into family since the inspiration came from a sibling on the team, however, I kept it as a separate category due to the nature of the storytelling, which leaned more towards documentary than personal narrative.